This pandemic has caused widespread speculation on the future of cities. Will we all telework? Will everyone move to places where they have more space? Politico, Wall Street Journal, and other outlets have gone so far to announce that this could mark the death of cities, with commercial areas a dry husk of former commerce.

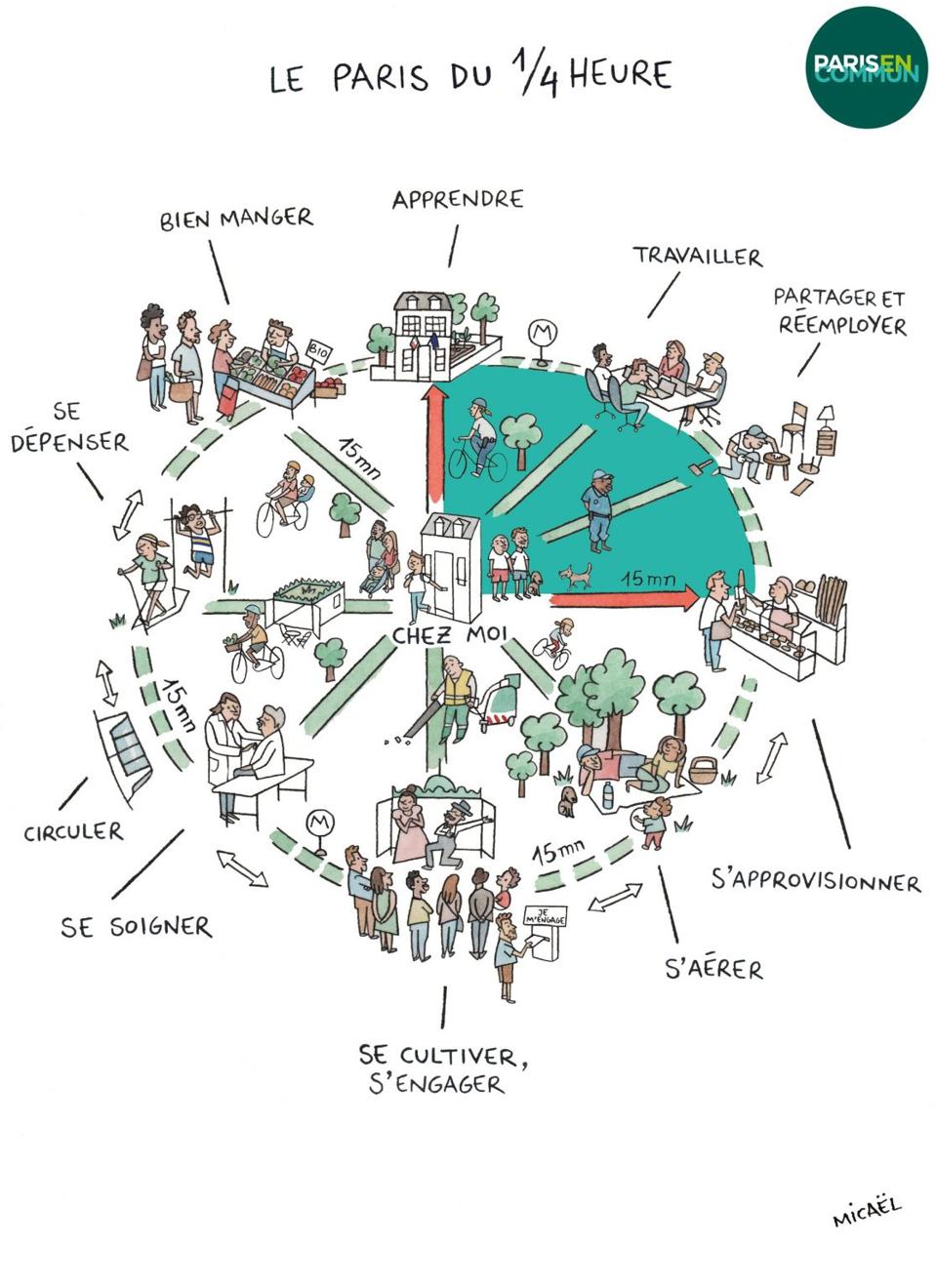

What these perspectives overlook is that not everyone has the means to leave, and that the pandemic may force cities to adapt in positive, sustainable ways. In January 2020, weeks before Covid-19 hit, Mayor Anne Hidalgo unveiled her plan to transform Paris into a “15-minute city.” It would redistribute the city into a cluster of neighborhoods where Parisians have access to everything they need within 15-minutes of travel by bike or foot from their home. The plan calls for streets closed to cars, intersections into pedestrian plazas, gardens in parking spots, and more.

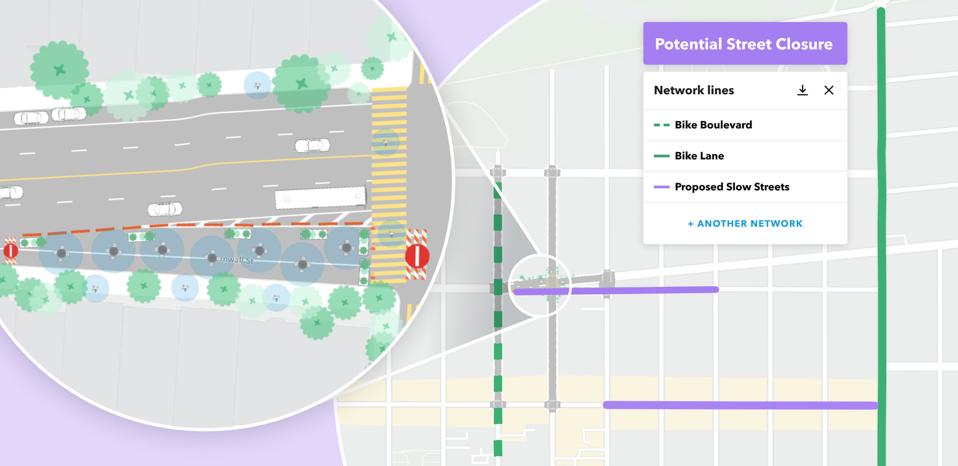

Sound familiar? During quarantine, cities created ad hoc solutions intended to serve residents who needed to move—often in their neighborhood. We saw an iterative wave of quick changes including “slow streets,” “streateries,” and the prioritization of bike and pedestrian networks.

Transit agencies had to plan specifically for essential workers, typically off-peak commuters, low-income, female, black, indigenous, or people of color. If ridership equalizes throughout the day, maybe it no longer makes sense to double train or bus service during morning and evening commute peaks — and we should instead run steady, dependable headways for a longer day span. For those of us who have long fought for mobility of the car-less, of low-income BIPOC communities, this is not the death of the city—it’s a refocusing on the needs of those underrepresented that will make our cities more resilient.

In a span of a few weeks, cities like Oakland, Somerville, Sydney launched quick-build projects as … [+]

The Rise of Neighborhood Centers: A Different Kind of Commute

The cost of transportation serving primarily peak commuters is under-researched and thus not widely understood. Caroline Criado Perez, the author of Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, highlights research in Sweden which examined snow plow route prioritization effects by gender. Plowing had always started with major roads and later got to smaller neighborhood streets. They found that men typically commuted via major roads, whereas women used local streets frequently to walk with kids in tow, care for family members, and more. By reversing the snow plow prioritization, the number of women admitted to the emergency room and subsequent health care costs actually dropped.

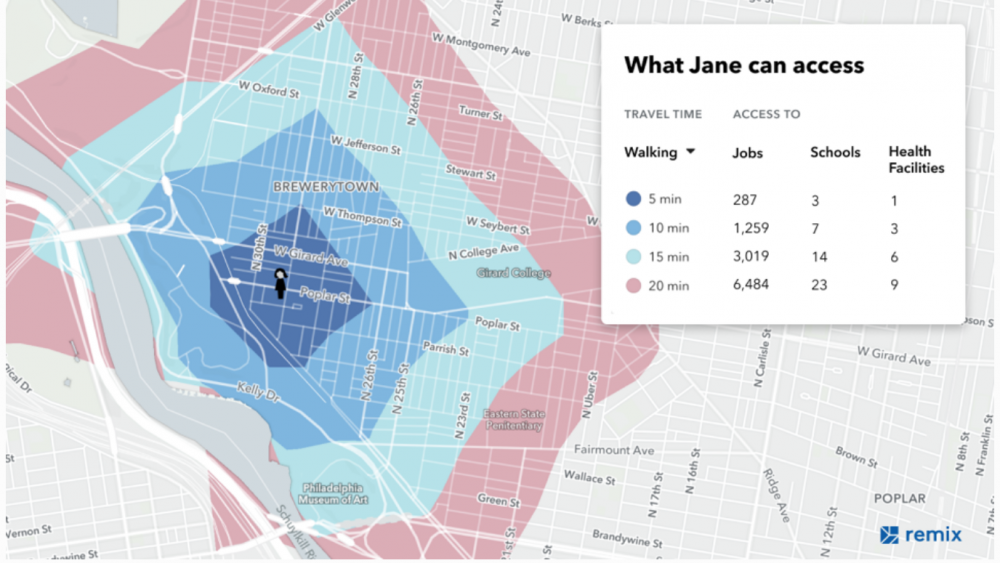

An increased focus on neighborhoods gives us the chance to plan for the non-peak commuter — such as parents taking kids to and from school, shift workers, caregivers, seniors — and the results could be tremendous for health and well-being, much akin to the promise of the 15-minute city.

Refocusing on Travel Patterns Long Neglected

Some city agencies and transportation departments are re-examining travel patterns and needs. Los Angeles released a report on pandemic commutes which specifically compared travel trends between low-income and affluent neighborhoods. They also surveyed transit riders and found that almost 50% are depending on transit to run essential errands.

In a recent webinar with the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, SFMTA Director Jeffrey Tumlin, and myself, Tumlin described a notable change: transit ridership has shifted to local routes connecting neighborhood centers, rather than downtown routes primarily serving the financial district. Despite the pandemic, San Franciscans are still traveling between neighborhoods to access amenities and services. Urban activity is still very much alive, just more distributed. In response, SFMTA is providing more local route service, which has been a challenge: “It often takes a lot more staff time to do what is equitable rather than what is easy,” Tumlin said, but he adds that doing so will help the city survive and recover.

Moving beyond “the peak commuter”

The pandemic has forced our cities to think about how to get folks in and around their neighborhood needs safely. As major cities seek to create an inclusive plan for the future of all of their residents, it’s clear that this is not the death of the city, it’s a push to serve the needs of residents who are not traditional “peak commuters.” That refocusing has brought more right-of-way for cyclists and pedestrians, more street space for gathering outdoors, and more studies focused on those who have been underserved — investments that will surely lead to greater resilience and bring us closer to the promises of the 15-minute city.

Tiffany Chu is an environment commissioner for the City of San Francisco and the CEO of Remix. This piece was co-written by Rachel Zack and Janice Park.