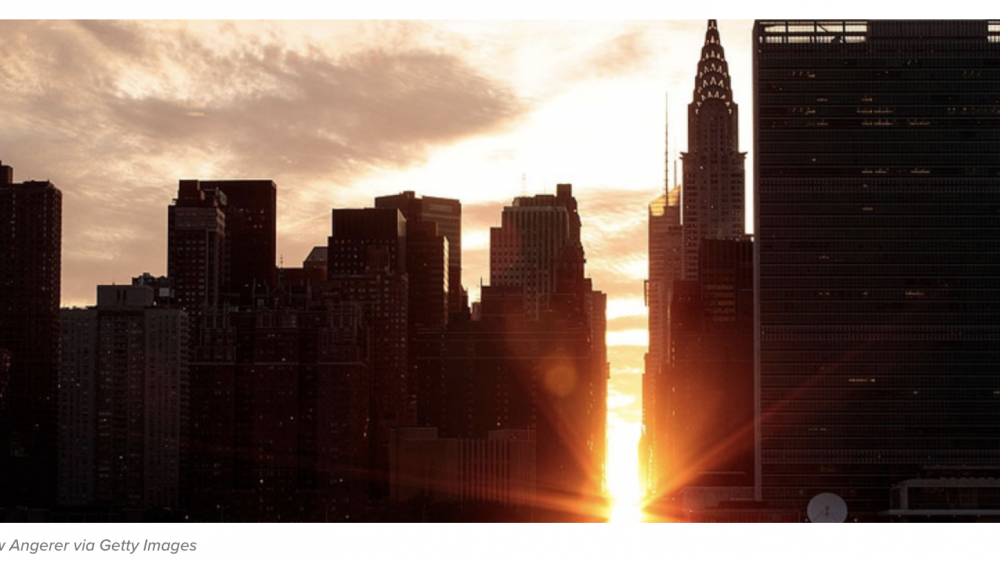

Queens may be a New York City borough, but it has smart city ambitions. The densely populated district aims to become a “smart borough” through an initiative that emphasizes tech and infrastructure modernization.

The effort is led by Queens President Donovan Richards Jr., who was elected last year, and his staff. Its key focal areas include connectivity, mobility, sustainability and the future of work, said Rhonda Binda, Queens deputy borough president.

Binda suggests that boroughs need their own strong infrastructure to successfully integrate into the city’s broader plan. In addition, NYC’s smart city efforts tend to center on Manhattan and often do not provide comprehensive inclusion of the other boroughs, she said.

“[W]e know that each borough needs to focus on modernizing its infrastructure in order to benefit and participate in any overall city effort,” Binda said. “Thus far with the city’s overall smart city efforts, we have seen the outer boroughs left behind… By the time the technology reaches the outer boroughs it is often outdated.”

She cited the Citi Bike bikeshare program’s Manhattan focus and ineffectiveness at addressing transit deserts in the boroughs. Plus, the program now competes with new mobility options such as e-bikes, scooters and mopeds — and those modes are still missing the mark on meeting mobility needs throughout the boroughs. She also said LinkNYC, a kiosk-based communication network offering free Wi-Fi, has been ineffective at closing the digital divide.

A major goal of the smart borough initiative is to grow the tech sector. Queens hasn’t benefited from New York’s tech presence and venture capital to the same degree as other local areas, Binda said. The Queens Chamber of Commerce launched the Queens Tech Council this year to stimulate post-pandemic growth both for tech startups and established businesses.

“Even though we’re part of a larger ecosystem, we’re not accessing it,” Binda said. “Our companies haven’t been plugged in… We’re trying to build stronger connectivity to that network so they can grow.”

Another aspect is to boost Queens’ connectivity. The borough launched a beta-stage digital community platform for residents to connect based on their interests. Internal testing is taking place this summer and the goal is to open the platform to residents across the entire borough this fall.

Mobility is another focal area, and Richards is advocating for more investments in various modes of transportation and related infrastructure. The smart borough effort promotes modernizing Queens’ transit network to provide additional mobility options such as shuttles, bikes and buses in areas where there are fewer options. They also hope, at some point, to convert the vehicles at the Queens Borough Hall to an electric fleet to promote sustainability.

The idea of a smart borough sounds promising in theory.

“I think it’s brilliant — the fact that a borough doesn’t want to wait for the bureaucracy and the blessing of a larger entity. I think it’s fantastic that they’re doing it on their own and taking the initiative,” said Karen Lightman, executive director of Metro 21: Smart Cities Institute at Carnegie Mellon University.

But there is a flip side.

“To be cynical: The term smart city, what does it mean? What is a smart borough?… What are they actually doing? How much of this is really a deployment of technology? How much of this is a desire to be seen?” Lightman said. “I love the concept of going on their own. I also do worry about what is actually a smart city or smart borough.”

Binda says that many smart city failures occur when projects focus on technology-driven methods instead of taking a people-centric approach from the start. Queens is building a coalition to reflect its diverse perspectives and needs, she said.

Other communities throughout the country have stepped out from their greater metropolitan areas to become micro-smart cities. Lake Nona, near Orlando, Florida, dubbed itself a smart community and tested an autonomous shuttle service. And a neighborhood in Atlanta became the first “smart neighborhood” with energy-efficient, technology-rich homes. But such smart community efforts tend to be much smaller than the one in Queens, which has a population of about 2.2 million people.

Cities typically have the most success in achieving smart city efforts when they are anchored by a cohesive, strategic, comprehensive plan, experts say. There has been a wave of deliberate smart developments over the past five years, in which cities including Philadelphia drew up roadmaps to guide their smart development and hold themselves accountable. New York City has a formal smart city plan as well. Cities including Seattle have hired a person dedicated solely to coordinating the complex smart city policies and projects across departments.

Piecemeal projects that are not backed by a wider strategic plan sometimes fizzle. For example, last year Sidewalk Labs abandoned its Quayside smart project in Toronto. This year, Portland Metro severed ties from smart city work with Replica, a Sidewalk Labs spinoff company, due to data and privacy disagreements.

Lightman emphasized the need to be thoughtful, intentional and iterative in creating and implementing a plan when applying a tech-forward approach to elements like transportation and infrastructure improvements. She also recommends spending a lot of time identifying the proper stakeholders and supportive partners.

“You can use tech to improve that, but you can’t do it in isolation… You can spend a lot of money and effort and it still completely implodes,” Lightman said. “How are you improving? How are you changing? How are you ensuring this is done safely and equitably in every neighborhood?”

Overall, Lightman praises the idea of Queens’ desire to be a smart borough, while also cautioning that how communities devise, implement and advertise their smart city strategies matters.

“I applaud them, but buyer beware. It’s not for the faint of heart. It’s hard,” Lightman said. “I’m excited for them. I think this could be fantastic.”